The Way of the Heartbeat, Part 2

"Dream of the Spirit Berries"

Binaakwii-giizis (Moon when the leaves fall); October 12, 2017

An allegorical tale about a brave Mississauga girl who had a dream that restored life to the starving bears...

“It is so sad that the Anishinaabeg, who are such a peace-loving and nature-loving and family-loving people, could experience so much pain and at the same time not even had a clue as to the overall hurt and healing that would eventually come.”

- Simone McLeod

Boozhoo, aaniin!

Welcome to part 2 of the blog series titled The Way of the Heartbeat, in which I connect my storytelling jewelry and graphic art, along with artworks of kindred artists, with the ancient teachings that my ancestors have passed on since they still lived in the Dawn Land in the East - and probably as long as our People have been walking the face of our beloved Aki, the Earthmother.

This story, the second in the series, is told in the old Anishinaabe tradition of aadizookewin ("traditional storytelling"). It is an aadizookaan, a "sacred story." Traditionally, once an aadizookaan is being told and the supernatural beings (called aadizookaanag) are called upon and invited to enter the human stage, the story transforms into an aawechigan: which is really a parable, typically with a moral undertone.

In the ancient oral storytelling tradition of the Ojibwe Peoples, aawechigaanan, or rather, aadizookaanan turning into aawechiganan, are supposed to be shared only when it is considered appropriate. This means always in a ritualized fashion and never in a casual manner. Oral storytellers typically reserve the aadizookaanan/aawechiganan strictly for the long wintermoons, preferably in the evening after dinner around campfire. One of the reasons for this seasonal restriction is that, in order not to offend the aadizookaanag (the protagonists of the story), and to preserve their alledged transformative powers, it is deemed unwise to talk about them outside the winter season - which is considered to be the time the aadizookaanag are asleep.

The story that I share with you today is based on an idea, or rather, a vision (although she herself is too modest to call it a vision) that my artistic partner Simone McLeod had in the fall of the year 2016 and which she generously shared with me, asking me to write a story about it. The idea/vision she had is based on a harsh reality she found herself confronted with when she, in the Moon of the Falling Leaves, 2016, chose as her residence the town of Blind River, Ontario. The local Omisi-zaagiwinini Anishinaabeg¹ call this place Biniwaabikaang, a name referring to a narrow, sloping rock along one of the river branches in the area and that is situated on the shore of the North Channel of Lake Huron.

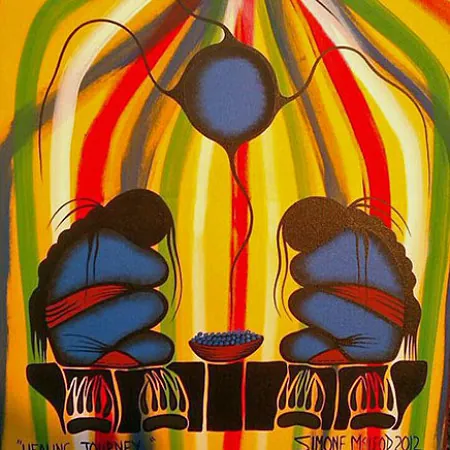

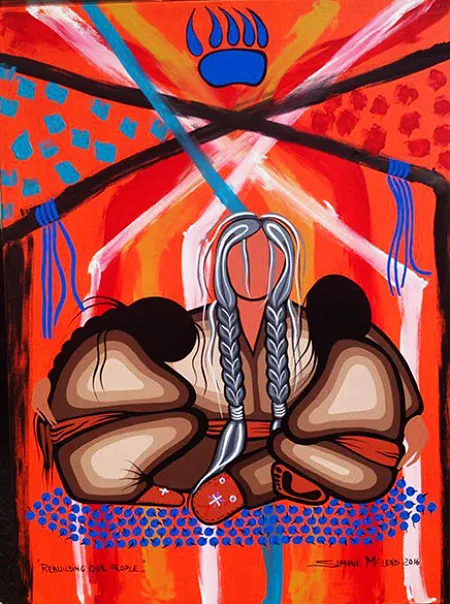

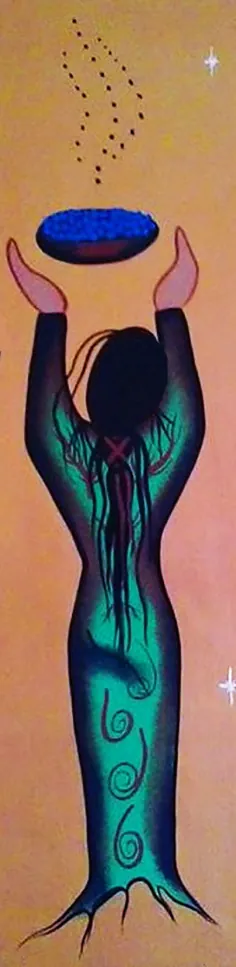

The story we tell today is accompanied by nine beautiful acrylic canvases (or details of canvases) painted by Simone McLeod as well as by a necklace that I created at my workbench some time ago and which I titled Manidoo-miinan Izhinamowin - which is Anishinaabemowin for "Dream (or Vision) of the Spirit Berries."

Bear Spirit Poem

"I saw you there

Your final rest

Your great paws

Upon your breast

While the sun shone

With spring day smells

My eyes did rain

As teardrops fell

I give great thanks

Tried honouring you

Wishing some day

All the people knew

What courage you held

In your huge heart

On this sad day

Our mother you did part

For those of us

Who do see you

Your tears will shine

On mornings dew

Farewell my brother

I'll not soon forget

The day I was born

Is when I first met

The lodges that stand

Hidden deep in our mind

Someday they'll be open

Our way we'll find..."*

The Sacred Tale of Little Blueberry Woman and the Bears

Once upon a time, in a village situated at a river branch close to the north shore of Nadowewi-gichigami (present-day Lake Huron), there lived a girl with curly black hair and beautiful almond-shaped eyes who belonged to the People of the Omisizaagiwinini-Anishinaabeg (Ojibweg who live at the Great River Mouth). Her People knew her by the name of Miinensikwe (Little Blueberry Woman). She was a member of Maanameg doodem, the clan of the Catfish People - who, along with other fish clans and those of turtles and snakes, are traditionally charged with Teaching and Healing.

From her earliest youth Miinensikwe, who was known to walk the earth barefoot all year round, was observed to be introverted and pensive. Even in infancy the girl seemed different from her siblings and the other children of her village; and as she grew older her character appeared more strange and more wonderful. Even before she attained the age at which Anishinaabe children enter upon a period of puberty rites and fasting she was well-known for her artistic nature and qualities, and it escaped no one’s attention that she spent much time in solitude and fasting. Some people even whispered that she was banaabekwe, a person belonging to the other-than-human-class, having the features and outer form of a female human being but in reality possessing at least some qualities of manidoo (a spirit). Whenever she could leave her parents' wiigiwaam she would venture off - sometimes at night - to remote glades in the dense woods that covered the shoreline of the lake, or sit at a place that her People called Biniwaabikaang, upon a steep and narrow rock that overlooked a river branch of the river that nowadays is called Blind River. It was in such sacred places that Miinensikwe sought meaning and self-discovery by addressing the spirits of the Universe and by regularly invoking her makwa bawaagan, or bear guardian spirit. More often than not she would feel the urge to use red ochre to paint in the presence of the spirits her dreams and visions on the rocks and cliff walls that bordered the river. Even at a young age, Miinensikwe was the philosopher and the artist of her People…

It happened to be that in those days, the miinagaawanzhiig, or lowbush blueberries, were the most numerous of all the berries and the deep purple brilliance of these berries used to be unrivaled; so beautiful were the blueberries to the spirit and senses of Miinensikwe's People that they held them in high regard.

Needless to say, the blueberries were the favorite forest nibble of the makade-makwag, the black bears, and since bears capture the essence of mino-bimaadiziwin, or a good and wholesome life, thus symbolizing transformation and renewal – which is why the Midewiwin Lodge regards bears as powerful guardian spirits –, the fruit of the blueberry bushes was traditionally offered in combination with purification and healing rituals, such as those performed in the sweat lodge.

However, over time the sweet tasting blueberries, which flourished by the myriads along the shorelines of the lake and the river branches, became so common that tayaa! the Peoples of the Omisi-zaagiwininiwag forgot to mark their remarkable flavor and nutritious and medicinal qualities and their wild and juicy taste! Ehn, they even became blind to the dazzling deep blue color of the berries and the profuse white blooms that had pleases the eye of many generations before them!

The blueberries lost their charm to the Omisi-zaagiwininiwag; before long even the men and women of the ancient Lodges stopped using them in their sacred ceremonies!

Miinensikwe's People seemed to have taken the blueberries for granted!

And this is why, when the miinagaawanzhiig, the blueberry bushes, started to decline in number and the richness and brilliance of their flowers and fruit diminished, almost no one seemed to care, almost no one deemed it necessary to become alarmed. After all, why should they be concerned? Was the cycle of scarcity and abundance not just a part of the natural order of things, a logical development in the process of bimaadiziwin, life itself? Was the natural cycle of decay and regeneration not something that applied to their relatives the blueberries as well? Yet atayaa! Woe betided Miinensikwe's People! It was by reasoning like this, that the Omisi-zaagiwininwag began to overlook the fragile nature of the balance that exists between all living things in general. Nor did they fully understand that the Outsiders who had come to their country and introduced the concepts of ego and greed and immoderacy had already invaded and poisoned their thoughts and actions!

Enh, the People of the Great River Mouth, who were once the wisest of all Anishinaabe Peoples, seemed to have taken over the ways of the Invaders.

Many had begun to close their eyes to the original Teachings and to the age-old concept of circular dependency, that delicate fabric of the web that the Great Mystery had woven between plant, animal, and man...with truly dire consequences...

So, it happened that not before long the deer, foxes, rabbits, squirrels, mice, opossums, skunks, bluebirds, doves, cardinals, catbirds, mockingbirds, wild turkeys, and even the robins started to become affected by the scarcity of the miinagaawanzhiig that once had covered the earth as far as the eye could see, their fatness decreasing and their bellies screaming for food. Although the Omisi-zaagiwininiwag vaguely sensed that something was not quite right - the fur of makwa, the bear, became less rich and its meat tasted less sweet than it used to - it were our smart relatives the red foxes who were the first to be alarmed, and, naturally, in the longer term the other animals and birds and finally the bears themselves, since they too depended on the nutritious fruit that the miinagaawanzhiig used to yield in abundant quantities.

Eventually, one summer there were no blueberries to be seen anywhere! As soon as winter approached the Omisi-zaagiwininiwag, as many of their small animal relatives had almost become extinct and the makade-makwag (black bears) were all hide and bone and too skinny and weak to follow their yearly pattern of hibernation, finally started to worry and even to despair, and at last, everyone, humans and animals alike, became alarmed and started to blame each other. So it was in the time of year called binaakwii-giizis,² which would soon become known to our People as The Autumn of the Disappearance of the Blueberries, when more and more conflicts were reported and famine and desperation were at its highest, that a Great Meeting was called. Mizhinaweg³ were sent to all four corners of Aki (the earth) to call upon all the spirits and animals and Anishinaabeg to congregate and sit around a huge campfire; everyone was invited, everyone attended.

During the Great Meeting the delegates of the Anishinaabeg and of every animal being that roamed earth, sky, and waters, unanimously chose Makwa, the bear, as ogimaa, the First in Council. "Aaniin nisayedog ashi nimisedog gaye! (Hello brothers, and you too sisters!)" Makwa, who was not even a shadow of the mighty ogimaa he used to be, continued in a feeble voice that quivered with weakness: "Like you, I am worried about the extinction of our relatives the blueberries because they are becoming scarcer by the day and my People, as well as the deer and many of our little relatives, the winged ones included, are starving! What do you suggest we can do to help bring the blueberries back?"

The bear had hardly finished his sentence when the Anishinaabeg and the animals started a furious uproar that was heard all over Aki! Above the angry shouts and the wild accusations and public scapegoating the voice of the chief of the Odagaamii-Anishinaabeg whose name was Miskwaawaagosh (Red Fox) shouted: “Stop blaming and beating each other! I know who is to blame! It was the Outsiders, the waab-wagoshag, the white-skinned foxes, who ate all of the blueberries!"

An ominous silence followed the revelation by the chief of the Fox Nation, but then, within seconds the uproar rose again like a thunderstorm in spring and within seconds the poor snow foxes that were present that day were seized by the larger animals who started to beat them up and ferociously swung them around by their tails. So violent was the assault that the tails of the poor waab-wagoshag that survived the assault became stretched beyond recognition! Many snow foxes were killed that day!

But then, hoowah! something unexpected happened: Miinensikwe, the girl whom I introduced in the beginning of this story, stepped barefooted and seemingly fearless into the circle of the Great Council and spoke in a clear voice, as she addressed everyone present that day, “Wiinaboozhoo indinawemaaganidog awensiinhidog! Wiinaboozhoo niijii-anishinaabedog! Greetings my relatives of the animals! Greetings my fellow kinsmen! Atayaa! Daga! Good golly, I beg you! Do not kill the waab-wagoshag! Eye’, yes, it was the white-skinned race that invaded our land, idash eye’, and yes, it is their bottomless hunger for the fruits and natural resources and everything else that our beloved Earthmother yields that disturbed the natural order and caused the famine that even affects the lives of my own People. Eye’ geget sa, geget sa naa debwe awe Odagaamii-Anishinaabeg ogimaa, this is all true, the Chief of our relatives from the South, the Fox Nation, spoke the truth! But it is not the white-skinned foxes, the relatives of the red and black and silver foxes, who so kindly visited us from the North in order to be present in this Council, who are to blame! The light-skinned Invaders who we call the Gichi-mookomaan (Big Knives) are to blame for the demise of our Ancestral Ways and for the starvation of our relatives the bears, and no one else!

But remember my People, the disappearance of the blueberries and the starvation of the bears is not something you can hold the white-skinned Outsiders whose ancestors came from across the Great Salt Sea solely accountable for. The disappearance of the blueberries is your fault too! Had you not embraced the destructive ways of the light-skinned Invaders, had you not forgotten about the original Seven Instructions of the Great Mystery that our ancestors handed over to us and had you not forgotten to care for and look after our relatives the blueberries, had you instead continued to honor the old traditions and the offering of the berries in our Lodges, then the poor bears would not be starving and yet have enough fat on their bones to be able to follow their annual hibernation path. But instead of sticking to the Ways of our ancestors, many of you left the Good Red Road and chose to follow the selfish ways of the Invaders; many of you stopped going to the Lodges and many of you became indifferent to the faith of the blueberries and the bears... indawaaj daga nindinawemaaganidog awensiinhidog, niijii-anishinaabedog, so my animal relatives and my fellow kinsmen, please! stop looking for scapegoats and leave the poor snow foxes be and listen to what I have to say...”

Then, after a brief silence, the girl calmly spoke of a dream she had had, three days before the Great Council congregrated at the shore of Naadowe-gami. The spirit of a black bear had appeared in this dream, handing over a wiigwaasinaagan4 filled with juicy blueberries.

The bear grandfather had spoken the following words to the girl:

"Wiinaboozhoo indaan…ninga dibaajim. Greetings my daughter. Let me tell you a True Story. A long time ago, even before the light-skinned Outsiders invaded Turtle Island, the Anishinaabeg left the shores of the Dawn Land bordering the Great Salt Sea in the East to embark on a long journey toward the Land of Many Lakes where you live now. This journey, which lasted many generations, was marked by Fires. By the end of the era of the First Fire, not long after reaching the southern shores of Miishii'iganiing5 and Mishigamiing,6 the migrants became lost and their once strong sense of oneness shattered, and they split in a northern and a southern branch. The southern branch of Anishinaabeg even divided into three seperate Nations! Then, one day, a boy belonging to one of these three Nations - as had been predicted when the Anishinaabeg still lived in the Dawn Land - dreamed of islands in the form of Stepping Stones. Along the migration path the direction of the Mide Miigis (sacred shell) had been lost, the Medicine Lodge had diminished in strength, but fortunately, the boy's dream about the Stepping Stones pointed the way back to the traditional ways of the Dawn Land People. Like a prophet in the Dawn Land had predicted, now the time of the Second Fire had arrived:

"A boy will have a dream and the dream will show the direction to the stepping stones to the future of the Anishinaabeg peoples."7

Hereupon, your People, who nowadays call themselves Misi-zaagiwininiwag, who had migrated along a more northerly route than most of the other Anishinaabe groups, called for the three groups of the southern branch - whom they regarded as the Lost Ones - to return to the Mino-bimaadiziwin Miikana, the Path of the Good and Wholesome Life, and entrusted them with the task of forming a political confederation, called Niswi-mishkodewin or Council of Three Fires. The dream of the Stepping Stones, which came from the fasting boy, proved the vision and leadership of his People, and this is why the Boodewaadamiig - such was the name of his People - were appointed as the oboodawaadamoog (hearth tenders) of the council of the Three Fires. However indaan, it were your People, the Omisi-zaagiwininiwag, who had urged the southern branch of Anishinaabeg to reunite by rekindling the age-old beliefs from the motherland in the East; it is your ancestors who were instrumental in guiding the Lost Ones back to the Good Red Road and who were responsible for the restoring of the Original Seven Teachings of the Great Mystery! And since it is your People that should have the credit for rekindling the Ancestral Fires and for guiding all Anishinaabe Peoples into finding back the Good Red Road and since you, indaan, have proven to be receptive to the ways of your ancestors and to have not forgotten the proper ways to address the Spirits of the Universe, I chose you to relate to your People the True Story that I tell you today.

Today, we live in the era of the Sixth Fire indaan. In the era of the Fifth Fire – during which time your ancestors were still roaming the shores and islands of Gichi-ogimaa-gami (Lake Superior) -, a time came of great struggle, but unlike the era of the Second Fire in which the threat had originated from within their own ranks, this time the danger came from the outsiders - the white-skinned race that arrived from across the Great Salt Sea in the east.

We live in dangerous times and false prophecies and the moral negligence of the era of the Fifth Fire have already started to destroy many lives and communities. Mind you indaan, your People are on the brink of a total destruction of the Anishinaabe way of life."

“Those deceived by the false promises of the Fifth Fire will take their children away from the teachings of the Elders. Grandsons and granddaughters will turn against the Elders. In this way the Elders will lose their reason for living ... they will lose their purpose in life. At this time a new sickness will come among the people. The balance of many people will be disturbed. The cup of life will almost become the cup of grief.”

The lighting of the Seventh and the Eight Fire

After a brief silence the dream bear continued to speak: "This is why I now hand over to you this bowl filled with Manidoo-miinan (Spirit Berries), indaan. Through these Spirit Berries I want you to help restoring the balance of life. In order for you to do so I want you to first save my People, your relatives of the once powerful Bear Nation; the berries will provide my People with the nourishment they need to survive. Then I want you to go to your own People, the Anishinaabeg, and tell them about your vision, thus providing them with the spiritual nourishment they need in order to restore the natural balance that was still present before the light-skinned human beings who came from across the Great Salt Sea in the East invaded Turtle Island - and that was still intact before these Invaders started to poison the earth, the waters, the sky, and the spirits of the Anishinaabeg. I want you to remind your People that the spirit of excess and greedy ways of the Newcomers still cause great and continuous suffering and death to all the Earth's People. Today, indaan, I want you to light the Seventh Fire."

As soon as the bear grandfather had handed to the girl the bowl of blueberries he disappeared and the girl found herself sitting in a Lodge made of a round, open structure made of poplar saplings and decorated with colorful ribbons the colors of red, green, yellow, and black. As she sat there looking around in wonderment she noticed sitting in the center of the Lodge the bowl filled with the Spirit Berries that the bear had given to her in the first part of the dream, and before she knew it a long line of bears, who looked hungry and feeble and their once mighty body masses reduced to sagging pelt and bones, entered the eastern door of the Lodge. The girl watched in wonderment as the hungry bears, whose fat storage had been depleted dramatically, started to feast on the blueberries, and as soon as the bowl was empty the bears stood on their hind legs and, as they regained their former body mass, walked to the western door which they used as an exit, and left toward the setting sun, finally ready to start their yearly hibernation...

As soon as she had concluded her story about the dream bear who had offered her the bowl of Spirit Berries, the brave Misizaagiwinini girl whose name was Miinensikwe stopped talking and a deep and long silence filled the open space adjacent to the Lake. All the people and animals present that day were humbled by the simple power and truth of the dream that had just been related to them; everyone, not just the bears, felt an all-pervading healing presence touching their bodies, their spirits, and their hearts. The barefooted girl, by sharing her dream about the Spirit Berries, had taught everyone present a powerful lesson in the most modest of ways. Enh geget, the story about the bears held a valuable lesson to all the Anishinaabeg present that day, and to all the Anishinaabeg who live today, in the time of the Seventh Fire: it is not too late for us to honor the berries and the bears; it is not too late to turn from the materialism and greed of the Newcomers who had invaded our land.

It is not too late for us to choose the path of respect, wisdom, and spirituality that our ancestors blazed for all of us and for our children and grandchildren and the generations yet to come. It is not too late to make drastic changes in our lives and our communities, beginning today and for the benefit of the Earth and all that lives on it... Now is the time for us to take our responsibility as individuals and as a People to work together and light the Eight Fire...

"Only then, if the People of all colors and faith choose the right path, a path of respect, wisdom and spirituality, will the Seventh fire light the Last Fire, an eternal fire of peace, which will unfold an era of spiritual illumination…”

The symbolism of the necklace

The necklace, which I titled Dream of the Spirit Berries, symbolizes hope. The design of the necklace tells the True Story that the Makwa Bawaagan (Bear Spirit Guardian Spirit) related to the brave Mississauga girl Miinensikwe as she was having a vision about the presentation of a bowl filled with blueberries that would eventually restore life to the starving bear population.

The turquoise and gold pendant that I crafted in the shape of a bear (and that was modelled after the traditional "bear fetish" design of the Pueblo Peoples from the American Four Corners area) symbolizes the girl’s vision. The beads of red coral of the jacla pendant attached to the necklace fastening represent the spirit berries that came to the girl in her vision and that saved the bears and other animals from extinction - and therefore safeguarded the future of her People.

The necklace also epitomizes Miinensikwe’s People’s long journey from the Dawn Land in the East to the Land of Many Lakes in the west, and which, during the era of the Second Fire after a long period of spiritual digression, eventually led to a rekindling of the age-old beliefs (the Seven Grandfather Teachings) from the motherland in the East. The coral beads of the necklace stand for the the legendary westward migration of the Anishinaabeg Peoples - and, in particular, for the Six Fires that mark the era in which the story of Miinensikwe and the Spirit Berries takes place.

The Kewa Pueblo style turquoise heishi beads of the jacla pendant that I tied to the gold necklace fastening (see the image to the left) relate to the dream of the Boodewaadamii boy about Stepping Stones (islands) that, in the time of the Second Fire, pointed the way back to the traditional ways of the original Dawn Land People; the seven white shell disks of the jacla represent the miigisag (seashells), ancient symbols of Life for the Medicine Lodge of the Anishinaabeg Peoples.

Finally, the sleek tripartite design of gold placed at the bottom of the necklace and right above the bear pendant, relates to the forming in the time of the Third Fire of Niswi-mishkodewin or Council of Three Fires. It is a symbol of the spiritual restoration and renewed political strength of the Anishinaabeg who in the era of the Second Fire had lost track of the Good Red Road.

Thus, in the era of the Sixth Fire, the Mississauga girl named Little Blueberry walked in the footsteps of the Boodewaadamii boy who a long time ago had helped lighting the Third Fire by relating his dream to the Anishinaabeg. It’s like the spirit bear related to Miinensikwe in her dream about the spirit berries: “Along the migration path the direction of the sacred miigis shell had been lost, the Medicine Lodge had diminished in strength, but fortunately, the Boodewaadamii boy's dream about the Stepping Stones pointed the way back to the traditional ways of the Dawn Land People.”

For this reason, the Anishinaabeg will always remember and honor Miinensikwe, the Little Blueberry, as the brave Mississauga girl who lit the Seventh Fire by relating to her People her vision that saved from extinction the blueberries, the bears, and many other relatives - including her own people, the Anishinaabeg...

Giiwenh. So the story goes about my friend's vision of the spirit berries... Such is the story of the brave Miinensikwe who reminded her People of their responsibility of maintaining the cycle of plant and animal life; such is the story of how the bears regained their strength again. Miigwech gibizindaw noongom mii dash gidaadizookoon. Thank you for listening to us today. Giga-waabamin wayiiba, I hope to see you again soon.

*Poem by Simone McLeod, May 2015

(O)misi-zaagiwinini Anishinaabeg: the Mississaugas

2 Binaakwii-giizis: the moon of falling leaves; the month of October

3 Mizhinawe: messenger. Plural form: mizhinaweg

4 Wiigwaasinaagan: birch bark bowl or dish or box

5 Miishii'iganiing: the Michigan lakes

6 Mishigamiing: Lake Michigan

7 See our blog post about the Migration of the Anishinaabe Peoples

> Read Part 3 of the series The Way of the Heartbeat: Blessing of Long Life

About the author/artist and his inspiration

Zhaawano Giizhik , an American currently living in the Netherlands, was born in 1959 in North Carolina, USA. Zhaawano has Anishinaabe blood running through his veins; the doodem of his ancestors from Baawitigong (Sault Ste. Marie, Upper Michigan) is Waabizheshi, Marten.

As an artist and a writer and a jewelry designer, Zhaawano draws on the oral and pictorial traditions of his ancestors. For this he calls on his manidoo-minjimandamowin, or ‘‘Spirit Memory’’; which means he tries to remember the knowledge and the lessons of his ancestors. In doing so he sometimes works together with kindred artists.

To Zhaawano's ancestors the MAZINAAJIMOWINAN or ‘pictorial spirit writings’ - which are rich with symbolism and have been painted throughout history on rocks and etched on other sacred items such as copper and slate, birch bark and animal hide - were a form of spiritual as well as educational communication that gave structure and meaning to the cosmos that they felt they were an integral part of.

Many of these sacred pictographs or petroforms – some of which are many, many generations old - hide in sacred locations where the manidoog (spirits) reside, particularly in those mystic places near the lake's coastlines where the sky, the earth, the water, the underground and the underwater meet.

The way Zhaawano understands it, it is in these sacred places invisible to the ordinary, waking eye that his design and storyteller's inspiration originate from.

Photo credit: Simone McLeod.

_______________________________________________